I Want Your Skull When You Die

ALLIE

It’s winter when she asks. Though it’s never really winter here. It’s mid 60s out, and we stand beneath a king palm tree.

“What if I asked you to go out to the desert?” She pauses. “To help me dig a grave?”

“Lou,” I say. “You’re insane.”

She tugs at her hair, short, but long enough for a stumpy ponytail, stiff-looking tendrils curled behind each ear. The night makes her face harsh, shadows for cheekbones, shadows for eyebrows, shadows for jaws, shadows for a mouth. It’s been a long time since I’ve really looked at Lou. It’s been a long time since she’s asked me to do anything.

“Just to see what it feels like,” is all she says.

I sit down on the curb at my car, my feet tucked between me and the front tire. “Remember that one time—” I start.

“God, is that all you ever say, Allie?”

“At the wind caves, the summer before fifth grade or something? And Jason—” and I realize what I’m saying and I stop. All I want to do is keep talking to Lou, even about Jason, even about death.

“I remember every time,” she says. And then: “Let’s go tonight.”

LOU

Before we make it to the desert, we pass the windmills—distant twirlers lined up along the mountain range. Big, hulking things that look useless. Stick figures, really. Waving scarecrows with limbs dismembered and rotating. Happy to be useless. Happy to be dismembered.

Allie looks down. That’s why I’m driving. She doesn’t like the windmills. Some weird phobia. She’s scared of the motion or something. It’s fucking weird, but also why I love her.

My car is old enough to have a cigarette lighter built into the dash. I push it in to give her something to focus on.

The windmills fall into the rearview mirror. Now it’s like they’re bon-voyaging us.

Good luck, girls.

The cigarette lighter pops out. Allie pulls it from the slot and the coil glows in the darkening cab.

“What if you put that on my arm right now?” I say. “Like, just fucking bam.”

“You’d probably die,” Allie says. “And then you’d crash. And then I’d die, too.”

We drive in silence. I’m thinking about my death, and also Allie’s death. Both of our deaths.

“Just kidding,” she says. She forces a laugh. “But it would probably hurt.”

ALLIE

We park on the shoulder of Interstate 8. This isn’t what I imagined. I imagined remoteness, bottoming out the car in a dried-up wash, wobbling through occotillo and wind caves to find somewhere secret and untraceable like movie fugitives. But we’re just here on the side of the highway and this isn’t the furthest away I’ve felt from Lou but it’s close, until she puts her palm on the small of my back and presses until I can’t help but start walking. I’m alone with her, and she’s pressing on my body, and maybe Jason is just still at home and not coming to hang out tonight, and isn’t this what I wanted all along? To belong to her in an unavoidable way?

“Lou?” I say, trying to think of a question.

“Look up,” she says. “I know it’s super basic but the stars are amazing out here.”

I glance up, and yeah there are stars, but I quickly look back at her, her neck craned into a long column as she stares upward. Her jaw is angled and busy, like a distraction. I touch it, three fingertips against the side of her cheek.

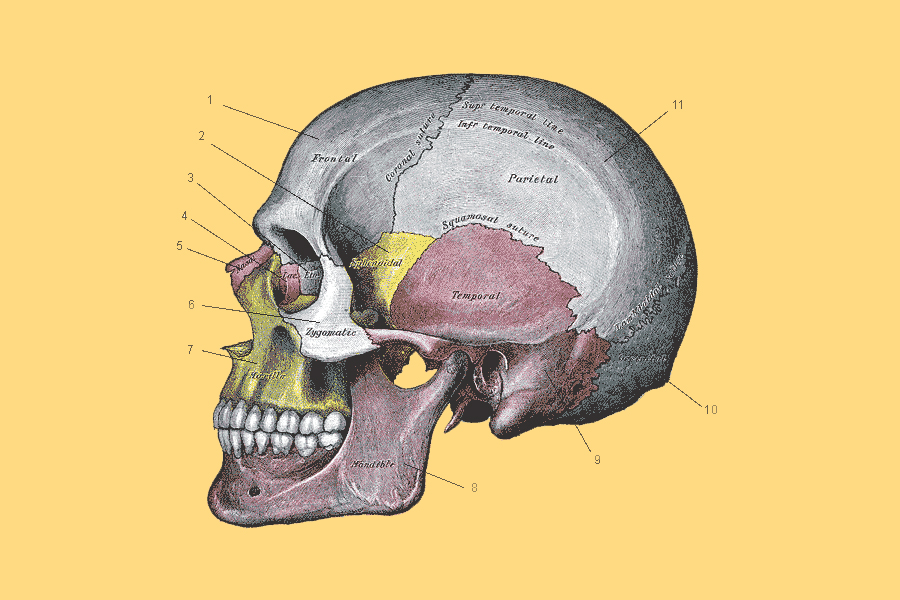

“I bet you’d have a nice skull,” I say. A line, a joke, an inside thing. A last ditch.

“You can have it when I’m dead,” she says.

“Wait here,” she says, stepping backwards away from me. “Sit down. And don’t move, or I won’t be able to find you. I’m gonna get the shovel.”

LOU

Allie’s no good with the shovel. I stare at the pitiful little dirt pile she’s created and wonder how anybody could be so useless.

“I’ve actually never used one of these before,” she says after she catches her breath.

“You mean a shovel?”

“Yeah.”

“How have you not—” I begin, but then stop. It’s not her fault that she’s weak. It’s not her fault that she’s never had to get her hands dirty. I somehow blame Jason. I can blame Jason for anything if I try hard enough.

“I mean, it’s okay,” I say. “Here, let me show you.”

ALLIE

I’m sweating, even though it’s just getting colder. The desert at night, our only winter.

“Okay,” Lou says. “I think we’re done.”

“It looks like you could probably hide a body in here,” I say. “Try it.”

Lou climbs in, flat against our fresh sandy grave. She’s still for a second, then jumps up. “Let’s go get it. The body.”

I laugh, because it’s funny, right?

She takes my hand, our fingers intertwining like when we were six, like husbands and wives. She pulls me to the car and it’s almost in slow motion when she does it, when she turns to look at me, her toothy smile flattening to serious, and then she spins on her heel to the trunk, wiggles a lever above the license plate. I know it’ll be Jason.

LOU

Allie’s reaction is animal. I imagined her freezing, choking, but she’s gone before I can even tell her that it’s okay. We’ll be okay.

She runs into the night. I follow her, blade in hand. I have trouble keeping up. After all these years, I never knew she was such a fast runner.

Julia Dixon Evans is author of the novel How to Set Yourself on Fire, forthcoming from Dzanc Books (May 2018). Her work can be found or is forthcoming in McSweeney’s, Pithead Chapel, Paper Darts, New York Tyrant, Hobart, Monkeybicycle, Barrelhouse, and elsewhere. She works for the literary nonprofit and small press So Say We All and hosts the Foundry reading series in San Diego. More at www.juliadixonevans.com.

Ryan Bradford‘s fiction has appeared in [PANK], Lockjaw, Hobart, New Dead Families and Vice. He was also the winner of Paper Darts’ 2015 Short Fiction Contest. He is the founder and editor of Black Candies, a journal of literary darkness, and his novel Horror Business was published in 2015.