Eight of the Sinks in the Home of Marshall Edson

1.

The one in the bathroom a few feet from where you first walked in. You had muddy hands, as was normal for a boy of your age. You’d somehow muddied them on the walk from your mother’s car to the front door. She had chided you, though it was less an expression of frustration with you and more to do with her bafflement as to where exactly the dirt had come from. She apologized to the man who answered the door, who was, it seemed, Marshall Edson’s butler or majordomo or some other kind of administrator. He gracefully indicated the door. Your mother bid you wash and waited for you outside. This sink was subdued, with a grey marble basin. There was a soap dispenser resting on it and a mirror above. The soap’s container was brand new; you had to pump it a few times for any sort of release. When you finished, you found your mother waiting for you outside.

2.

The one near the temporary office where your mother set up her laptop, plugging in the cord and adjusting a nearby desk lamp so as to illuminate the keyboard. She hadn’t been able to find someone to watch you in time and so she’d brought you here. She had been doing some sort of work for this man, Marshall Edson, for a little over a year now. I keep the books, she said, and for the longest time you believed your mother to be some sort of librarian. This room, at least, was full of books; you didn’t look at the titles, though. Your mother told you not to look. You did glance at a few and, on their spines, saw a language you couldn’t read. That, at least, settled your curiosity in a pragmatic fashion. You ran your finger down the exposed wood of one of the bookshelves. Enough dust had rubbed off on it that it required a quick washing; this nearby sink, in a small alcove without toilet or shower, did the trick. The water pressure in this one was low, and the cold water didn’t work at all. You pulled your hand away before the water could get too hot.

3.

The one in the hall adjoining the temporary office space. After you’d been there for forty minutes you indicated that you needed to urinate, and your mother summoned Marshall Edson’s majordomo. She asked if you should use the one near the front door, and the man shook his head. Plumbing issues, he said. A house that wasn’t what it once was, he said. And so you went into another bathroom, this one as nondescript as the first, and before you washed your hands you heard something that sounded like cricketsong coming from deep within the drain. As it was the month of February and snow had covered lawns for most of the preceding three weeks, this confused you. The grey freckles of the concave marble and the brass color of the stopper and then, that strange summertime song emerging from somewhere within. The song ended a few seconds after you noticed it. You washed your hands quickly and listened to see if the song would return; it never did.

4.

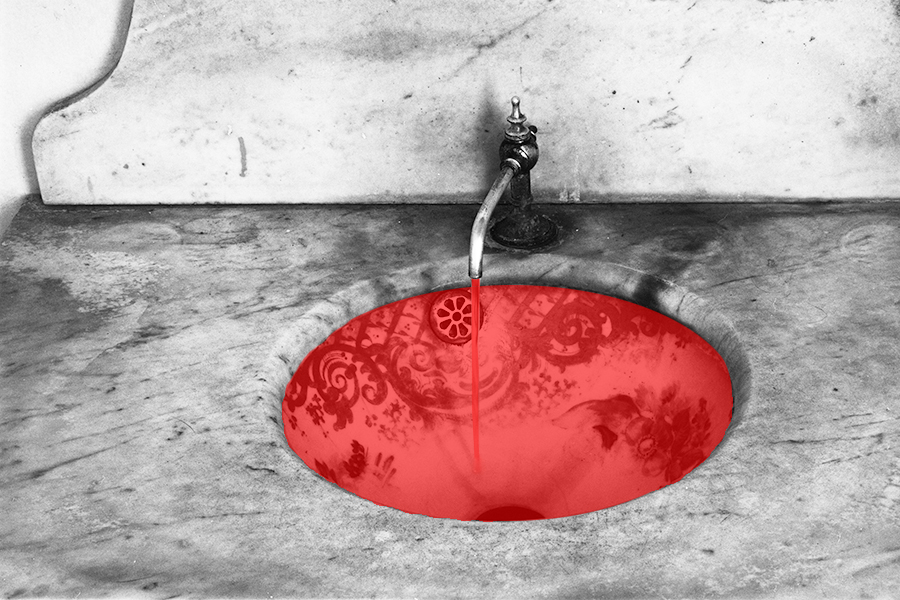

The one in the library’s alcove upstairs. You heard a car entering a garage and you saw a tension spread throughout your mother’s face. The majordomo arrived and told her that Marshall Edson was unexpectedly back, that he wanted to meet with her briefly; a cursory conversation, nothing more. So up she want and up you went. She told you it might be a while and handed you some colored pencils and a notepad. Still, you managed to turn your fingers blue and yellow and green within ninety seconds. The majordomo directed both of you to a library with an inner chamber and directed you to a bathroom within. This one was small, housing a toilet with a drawstring hanging above it and an ornate porcelain sink with strange images inlaid on the sides, a centaur bearing books and an angel gazing at something unseen, its face caught in an expression of alarm. You stood above this one for a long while, scrubbing and scrubbing. This, too, had a previously-unused bottle of soap beside it. You wondered what sounds might come from this drain, might move through the vents beside the floorboards, might emanate through the rafters. The room kept you waiting.

5.

The one in the parlor beside the library. Your mother’s meeting with Marshall Edson was going longer than expected. Your coloring no longer held any interest, and in the absence of anything else to do, you walked around the emptied library in circles until you’d dizzied yourself. Then you sat down. The house’s majordomo would periodically monitor you, entering the room briefly every few minutes to ascertain that you had not destroyed any books or injured yourself. After forty minutes of this you worked up the nerve to ask the majordomo if you could leave the library. Don’t go down the stairs, he told you, and don’t go up the stairs, and don’t open any doors. And so your cycles increased, surveying the illegible titles of the books and the swirls and arches cut into the wood of the floor and the balcony, some of the shapes echoing the figures in the sink downstairs. After another hour of this, you noted an ajar door in the hallway near the balcony that led to another bathroom. This one was grander; this one was outfitted with a sprawling sink, its basin akin to a baptismal font to which someone had attached plumbing. You could barely reach this one; it seemed surely designed for someone much taller, perhaps someone who even loomed over your mother or the majordomo. Here, too, you heard a sound issued from deep within the drain. This was less insectlike and more of a mammalian whisper. It was somewhere between the sound of a tin can telephone and the chanting of a priest in a formal mass. On the edges of the sink were the same angels and centaurs that you’d seen earlier. You couldn’t understand the language coming from the drain until, finally, you realized that you could. It was telling you a place you could go; it was telling you how to avoid the majordomo’s eyes.

6.

The one in which you washed its feet again and again, waiting for the sound of footsteps in the hall outside.

7.

The one in the kitchen, not far from the front door. When your mother returned she asked how your shirt had become dirty. She asked about the imperceptible stains on your sleeve; you were amazed that she noticed. You asked her how her work for Marshall Edson had gone and she said well, she talked of sacrifice, she talked of things yet to be done. The majordomo stood nearby as she moistened and soaped a paper towel and scrubbed the dirt from your shirt and shook her head.

8.

The one you never managed to find but heard as you walked through the hallways. That sound of a trickle, of water gradually filling its container. You heard it as you made your way through the highest level, the secret level, after your encounter with it. You were looking for another person, looking for some sign of life. You opened each door in turn but saw no bathroom, saw no facility that might cause the sound. The trickling continued. You walked through the hall and walked down the stairs to the grand hall by where the front door opened and you sat there for a very long time, as it was largely well-lit and there were windows out of which you could see the world outside, could know that there was still a world outside. And eventually your mother finished her work and found you and rubbed your shoulder gently, a gesture which always stayed with you and seemed to be a less maternal gesture than something else, a coach’s reassurance after a disappointing game, perhaps. But here was the thing: you kept hearing that sink. Not on the drive home, but as you lay in bed that night you heard that trickle, and the sound of water entering water, and the sound of water rushing over the bounds of the sink and onto the ground below and creeping along the floor. The first night this happened you sprung to your feet and rushed to your own bathroom and illuminated the room and saw nothing, no water in the sink, only a safe absence. The next night it happened you did the same thing, and the next, but eventually you became accustomed to its sound. You moved houses when you were fifteen and the sound of the sink endured there. You went off to college on a scholarship and you listened to the sound in your dormitory, though there were no sinks in your room, only a communal bathroom five doors down the hallway. You moved into your first apartment and you heard it there and you heard it in the apartments of many lovers and you heard it when you finally began cohabitating. You heard it in the apartment you moved into when you were single again and you heard it in the house you moved into with your spouse and every night as you tried to sleep, you heard it, that dreadful sound, the water drawing closer to the door, spelling ruin. Sometimes you think about going back to the house in which Marshall Edson had lived and sometimes you imagine tearing it apart. You know that, given enough time and the proper tools, this is a thing that you could do. But for now all you have is the sound and the form of the person you love beside you, and you wonder what the sound cost, and what the sound gave you, and what it might mean if the sound ever, ever, ever stops.

Tobias Carroll is the author of two books, Reel and Transitory. He’s the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn and writes the Watchlist column for Words Without Borders. He lives in Brooklyn and overcaffeinates regularly.